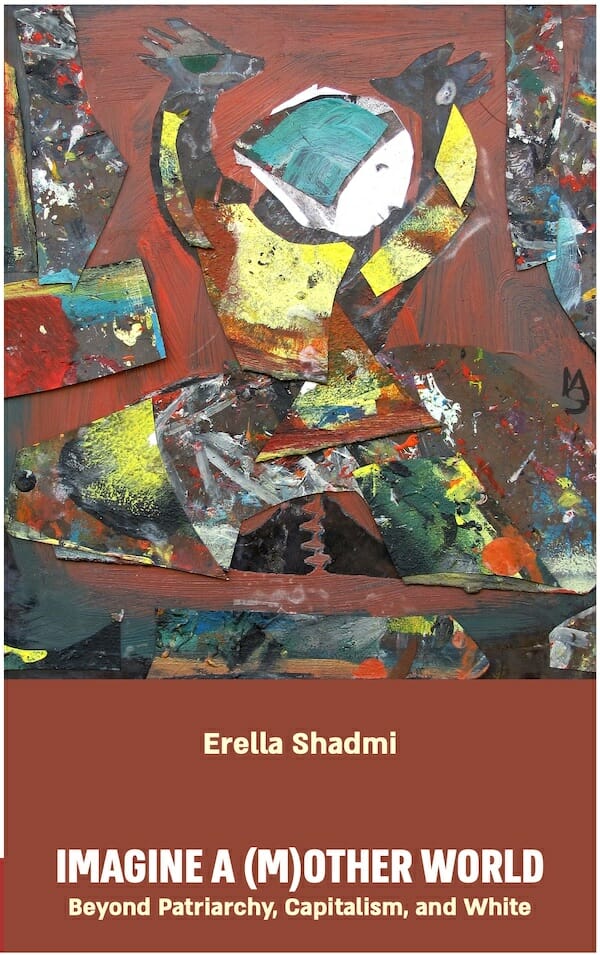

Imagine a (M)other World

Erella Shadmi

₪ 40.00

תקציר

This book addresses the multidimensional crisis facing western civilization and offers an alternative, innovative approach ‒ the Mother Logic as the basis for a counter-revolution to the western patriarchal order. This analysis comprises three parts: the profound failure of western civilization, rooted in the patriarchal rejection of the maternal and reflected in its wars and exploitation of nature; the matriarchy as a more viable social, political, and economic order; and the need for comprehensive and deep-seated change.

Drawing upon feminist thought, the maternal gift economy, the wisdom of indigenous nations, and modern matriarchal studies, this book presents an alternative paradigm that is not a utopian fantasy, but a path toward imagining a vision that can transform thinking and activism. While fully cognizant of the obstacles, the author offers a path toward realization of this vision in western society.

Dr. Erella Shadmi is a feminist activist, scholar, and peace activist and mother to Odin, an artist and designer. She headed the women’s studies program and taught the sociology of policing at Beit Berl College, and has published extensively on these subjects. Dr. Shadmi was co-founder of the Kol Ha-Isha feminist center in Jerusalem and the Fifth Mother women’s peace movement, and an activist with Women in Black, B’Tselem human rights center, Ahoti for Women, and the Isha L’Isha women’s center in Haifa. She is currently spearheading a campaign to establish a multicultural women’s museum in Yeruham and is active in global movements to promote the maternal gift economy and modern matriarchal studies.

ספרי עיון, ספרים באנגלית - English Books, ספרים לקינדל Kindle

מספר עמודים: 352

יצא לאור ב: 2023

הוצאה לאור: פרדס

ספרי עיון, ספרים באנגלית - English Books, ספרים לקינדל Kindle

מספר עמודים: 352

יצא לאור ב: 2023

הוצאה לאור: פרדס

פרק ראשון

Genevieve Vaughan,24 an independent, innovative researcher and philosopher, taught and still teaches me the maternal gift economy alongside a deep critique of the exchange system and capitalism. Vaughan identifies mothering as free giving in response to needs and therefore as an alternative economy. Infants need the free giving of grown-ups, as they cannot care for themselves. The motherly principle occurs in many aspects of our lives in the Western world—from gifts of nature (sun, light, air, water, resources), through human gifts of ideas, knowledge, and friendship to the Time Bank, blood banks, organ transplantation, voluntarism, solidarity networks, alternative communities, free stores, cooperative gifting circles, remittances made by labor migrants to their home countries, activism, and philanthropy—free giving that keeps expanding. Thus, alongside the market’s exchange economy, the gift economy is continually operating. It is important to see gift giving as an economy as it emphasizes the material basis of life and the care of this materiality by mothers. These two economies are contradictory, but they can coexist. However, the gift economy is silenced, denied, and exploited by the capitalist-patriarchal market, even though the market economy is contingent and dependent upon it.

The abundance of the knowledge economy on the internet has made it possible recently for many people to envision a material economy of abundance, where exchange, giving in order to receive an equivalent, is no longer necessary and, instead, gift giving directly to satisfy needs is the economic mode of distribution.

Exchange has a logic that contradicts the logic of direct gift giving; indeed, the market of Capitalist Patriarchy, which is built upon exchange, preys upon the gifts of all, creating scarcity by channeling them away from the needs of the many and transforming them into the profit of the few. This system, based on patriarchy and capitalism, has deprived us of the knowledge of the maternal principle and has enforced social and economic practices that contradict it. The system forces gifts upwards, routing their flow from the many towards the few, all the while emptying the environment and harming the fragile care of human and non-human species. Not only does it hinder progress towards a higher level, but it deprives future generations of what they need for full maternal humanity.

To create a new society and economy of abundance not only on the internet but everywhere, it is necessary to acknowledge the maternal (and matriarchal) basis of gift giving (see an extensive discussion of scarcity and abundance in Chapter 6).

Vaughan shows us that capitalism constantly strives to control all relations so that profit making may be enhanced, although it has not succeeded in doing so. Maternal gift giving practices are preserved in many of our human relations. She reveals that gift giving, by mothers and others, is not a thing of the past, “but has been continued, passed on, in the private realm of the home, as the Maternal Gift Economy” (Kailo, 2018).

Acknowledging and respecting the maternal roots of the gift economy are no less crucial. No, Vaughan does not see it as essentialist: Infants need the care of their mothers to survive, and fathers or other grownups can do mothering as well. Moreover, mothers need to be recognized as keeping this alternative economy alive and maintaining the possibility of using it across society—especially in the face of efforts to eliminate motherhood altogether (see Chapter 7), its sacredness, and its history of oppression and exploitation.

Recognizing the maternal roots of the gift economy also carries significant meaning for other reasons: It is true; it advances the definition of our species as Homo Donans; and we can recognize our connections with Mother Earth. If I can show that the source of economy is in the mothering gift economy (the breast is the first economic model and image, not trade or money), we have a way of understanding all patriarchal philosophy and economy as wrong because they leave out this maternal source or capture it in religions and other appropriative structures like the state. New understandings of epistemology and ontology are made possible by uncovering the patterns of the giving and receiving maternal model of the human. These lead to an altercentric basis for communication, perception, consciousness, and most other aspects of the human that patriarchy takes to be mysterious and to which it gives ever-new false answers.25

Instead of the accumulation of wealth and property, instead of an exchange system—ideas that are at the center of capitalism, that separate people and turn them into competitive, even hostile, individualistic, and antagonistic money pursuers—the gift economy paradigm connects people, turning them into generous and friendly figures, and builds communities. The gift economy paradigm exposes gift giving that exists at all stages and spheres of our life and is expanding these days to new areas, yet it is denied and exploited by capitalism.

As the roots of this free giving are in mothering, giving is evident among babies who show empathy from a very young age. And mothers all over the world, as well as other women and men who nurture and care for their home, children, spouses, and the community, preserve this economy until this very day. Its prevalence and centrality among all ages and societies leads to the understanding that Homo Sapiens are also, perhaps mainly, Homo Donans, that is, the gift-giving human being.

The fact that the values of care, necessary for mothering, are in opposition to the values of greed and domination, which have motivated the present economic crash, demonstrates that an economic system based on mothering could be a radical and positive alternative. Free gift giving is not limited to wealthy philanthropists or middle-class community activists; it is prevalent among poor and less-privileged people (Prochaska, 2006) and, of course, in indigenous societies, but also in Israel as I know from my own experience: As a single mother, I am not sure I could have raised my child without the support and help of my very dear friendly neighbors, most of them rather poor. This vast expansion of the gift economy today can be framed as a mothering movement, even when it is often implemented by men. Unfortunately, it is not clear to all yet that unilateral gift giving, necessary for mothering even in a society based on market values, is the building block on which both this transformative movement and capitalism are based.

***Gift giving is practiced on a daily basis in matriarchal societies, as the founder of Modern Matriarchal Studies, another of my great maternal teachers, Heide Goettner-Abendroth,26 taught me. Matriarchy is not the opposite of patriarchy. It is a society not of domination, but rather of peace, balance, cooperation, and equity, of responsiveness to the needs of others and living within spiritual communities that treat people and nature with respect. As such, matriarchy provides full and genuine security and liberty, including sexual freedom, to all its members. Matriarchal societies have a non-violent social structure, they exist without the exploitation of humans, animals, or nature, and all living creatures are respected. They are truly egalitarian, for they are based on gender equity; their political decisions are made by consensus, ensuring a peaceful life for all. Women and mothers are at the social and spiritual center (rather than on top!), thereby avoiding top-down control and creating an egalitarian society.

The deep structure of matriarchal societies—as developed from the meta-analysis of matriarchal societies (often under patriarchal influence today) conducted by Goettner-Abendroth—is based on its four levels:

Matriarchal economics (modes of production and distribution): a balanced economy with perfect mutuality, based on subsistence production (independent production) and gift-giving distribution; no private property, no territorial claims; only usage rights on the soil that is worked; basic goods and distribution are in the hands of women (i.e., the matriarchs).

Matriarchal social order: based on clans; non-hierarchical, horizontal order of matrilineal kinship (matrilinearity): residence very often in a big clan-house, house of the mother (matrilocality); shared mothering by sisters such that every woman is a “mother”; the brothers are the supporters of women, not the lovers or husbands; brothers are regarded as the closest relatives to the sisters’ children (“social fathers”); lovers and spouses either as guests overnight (“a walking/visiting marriage”) or during a short period, their home is their mother’s houses; each generation has its own “honor/dignity,” i.e., its own powers and tasks.

Matriarchal politics: decision-making by a complex system of councils (organized along the matrilineal kinship lines): clan councils, village councils, regional councils and, in some cases, inter-regional councils; all decisions are clan-based and made by consensus throughout the system of councils; the result—egalitarian societies of consensus.

Matriarchal culture and worldview: no organized, hierarchical religion with power centers, but rather tradition-based spirituality; spirituality is realized through a great variety of ceremonies and rituals, not static, but dynamic; no transcendence beyond the world, the world (Earth and Universe) is regarded as divine, i.e., divinity is immanent; the result—all is divine, all beings are equal, no hierarchy exists; “diversity is wealth”; everything/everybody is interconnected with all that exists; cyclical concept of time and life; everlasting cycles of life and death and rebirth; sacred societies/cultures, or cultures of the “Divine Feminine.”

Matriarchy exists today (e.g., the Mosu in China, the Minangkabau in Indonesia, and the Khasi in India), and existed in the pre-patriarchal era. Its remains may be found in all of today’s societies and religions, including Europe, Judaism and Christianity. In matriarchies, mothers are central to the culture without dominating other members of the community.

***Another maternal teacher of mine, the historian Barbara Alice Mann, a descendent of the Ohio Bear Clan, Seneca Iroquois, guided me through her indigenous legacy. Among the many ideas, concepts, and historic events I learned from her, I wish to emphasize a few:

Barbara Alice Mann presents the three pillars of her tribe’s constitution that were common throughout the matriarchal woodlands and had an important impact on the American constitution as well (Mann, 2004, pp. 161-164): The Great Law of Peace.27

Ne Gaiwiio—righteous thought/behavior

Ne Gashadenza—the sacred will of the people—the image of the “grassroots” is Iroquoian

Ne Skennon—public health/wellbeing

The economics of indigenous peoples, says Mann, is based on three main principles: abundance derived from nature and its proper use, partnership, and spirituality. The road was not a continuous exploitation of Mother Earth, but reward and conservation by many different methods that led to abundance all the time for all (see more on these principles in Chapter 6).

Mann also shows in her books (as does Goettner-Abendroth) how communal discussions— as well as decision making by consensus, which is the essence of the people’s sovereignty—are conducted.

Mann, furthermore, taught me about “the twinned cosmos of Serpents and Thunderbirds that delves into traditional understandings of the cosmos as a halved and interdependent whole, particularly as expressed in the iconic Twinships of Blood/water/earth Serpents and Breath/air/sky Thunderbirds. These existed in harmony, not enmity, for the purpose of cosmic balance, in star patterns and earth-bound mirrors of those patterns” (Mann, 2016, p. 12; emphasis added). Such a worldview, stressing complementary and collaborative rather than binary28 relations, is essential if we wish—as I wish—for a world of harmony and a new kind of relationship between men and women, in fact, between all sexualities that people might choose.

Mann (2003) continues to expound on the characteristics of European dualities:

Europeans operate on metaphors of ONE: There is one god, one way, one truth; people have one soul, one life, one true love. Two of anything necessarily indicates rivalry. In the either-or universe thus projected, the two are assumed to be at odds, with one fraudulent, for there can be only one legitimate version of anything. Each version must, therefore, try to destroy—or, at least, to subjugate—its rival. The Manichean dichotomy of Good vs. Evil is a perfect expression of this oppositional logic of the West. (pp. 173-174)

Humanity is understood as constructed of two distinct yet complementary halves (male-female and young-old), each complemented by the binaries within itself (age within gender/sex, and gender/sex within age). Thus, we have Two in Four. Furthermore, these binaries are part of complex geometric patterns that can be seen in Nature and Native symbolism.

Women occupy a central, significant role in Iroquoian society. The organizing principles of the woodlands Matriarchies hold that:

1. Creation was a collaborative project [that is, collaboration of humans and non-humans and of different generations].29

2. The Founder of Humanity was female [that is, women-led creation].

3. The primary human relationship is the mother-daughter bond.

4. The secondary human relationship is the sister-brother bond.

[All] eastern woodlands matriarchies feature a progenitrix...Women lead, and they are strong...Sky Woman of the Iroquois brought the sustaining crops with her from Sky World to seed on Turtle Island, while her daughter, the Lynx, invented other crops, including potatoes...The great matriarchies of Turtle Island also insist on...that women, alone, have the capacity to give birth...Women are celebrated as the sole life-givers, explaining one reason that the lives of women are considered twice as valuable as the lives of men...Because organized life arises solely from the woman, the strongest social bond is that of Mother and Daughter, a fact having massive implications for child rearing. First, in woodlands matriarchies, women have unchallenged rights to their own bodies. They have children, or not, at their own behest, and traditionally made use of abortions, even after European settlers outlawed them. (Mann, 2004, pp. 261-65)

Never forced to mate or breed, the woman chose her own time and mate. Neither was a woman confined to one man. In fact, in traditional times, marriages were not undertaken until after a young woman had sampled what was out there. From puberty to early adulthood, she was free to contract trial marriages, which might last one night or one year, at the woman’s behest. The man came to her longhouse, where he was under an obligation of cordial helpfulness to her clan mothers...free mate selection and easy transition from partner to partner is still the norm for woodlands women...Mother...leads. She has authority and is not afraid to spread strong medicine. [She] directly states her opinions and renders her decisions. She listens to comments, criticisms, and complaints, but her word, when it comes down, is respected. She takes bold action—and no one dares call her a ‘Bitch’ for it, because the men would take him out...True Mothering is made out of this woodlands mold, so that nurturing...is but one office expected of her. Yes, she nurtures, but she also guides, directs, advises, and orders life. If a response is called for, she requires honorable, respectful, audible replies. Thus, on the one hand, the child is protected, safe, and secure, while on the other hand, s/he is active, accountable, and mature. (excerpts from Mann, 2015)

And to add to the important words of Barbara Alice Mann, I would like to say a few words about mothers and mothering from the studies of Darcia Narvaiz:

By birth, the social environment of small groups of hunter-gatherers is quite different from that of Western societies such as the United States, and creates unique social and morally mature women. These societies have a culture that is at once individualistic and collectivist, highly enjoyable and cooperative, which cultivates natural virtues.

The practices that accompany the girl from her birth in small hunter-gatherer societies are responsiveness to the child’s needs, contact and being touched all the time, breastfeeding for at least two years, several adult caregivers, extensive positive support for mother and child, and free play in nature. These practices are associated with optimal functioning physiologically, psychologically and morally.

***South-African feminist poet, activist, and scholar, Bernedette Muthien, a descendent of the Khoisan people, opened my eyes to the centrality of communal life (which is central in both matriarchies and the gift economy, which encourages connections between people) and the concept of Ubuntu, meaning “I am because I belong” or, as Desmond Tutu said, “a human being is a human being through other human beings.” When I am part of relationships, I am never alone. I am connected to everything, to the world, to Nature. This sense of interconnectedness, of extended family and kinship, of community, is what defines Khoe!na or Ubuntu—people’s existence is critically tied to a profound sense of belonging (Muthien, 2008, p. 173). One person’s or group’s happiness or suffering is inextricably linked to another’s, and that one entity can never be truly satisfied or happy or enlightened without each member of that group being equally content (Muthien, 2008, p. 112). Ubuntu is part and parcel of the gift economy, referring to the collective caring about one another that is the cornerstone of all gift economies (as shown by the three pillars of the Iroquoian society mentioned above). Thus, contrary to Western cherishing of individualism, the community is important to me not less than myself. The Eurocentric “right to” is weighed against an “obligation to.” No individual right is at the expense of the community, and the community does not infringe on individuals. Individuals act with the community’s needs in mind. The community is especially crucial for mothering—as goes the Nigerian (Igbo and Yoruba) proverb that exists in different forms in many African languages: “You need a whole village to raise one child,” or as reflected in the concept of Motherism, developed by the late Nigerian Catharine Ocholunu to reveal the centrality of mothers in African culture (see Shadmi 2015, 2020). And, of course, free gift giving is the connecting glue among members of a community and between them and other communities and Nature in general. Ubuntu means consciousness of the principle of empathy between people, which is deeply connected to the spiritual dimension of gift giving.30

***Veronika Bennholdt-Thomsen, an innovative Austrian sociologist, whose decisive stand against capitalism’s drive for money, growth, and accumulation and its environmental consequences is remarkable, taught me the subsistence perspective derived from indigenous thought.

“Subsistence” means having what we really need for our lives. Yet the term “subsistence economy”—an economy focused on life’s necessities—is met with resistance. Intuitively, however, many people see that for quite some time something has gone fundamentally wrong with the dominant economy. But the longer we have organized our lives and expectations to fit the growth economy, the less we know what an economy organized around providing necessities could look like. For many years we believed that nothing was more important than making lots of money. Everything, every handshake, was aimed at making money. And for a long time there never appeared to be a problem to transform that money into tangibles like food, clothing, the roof over our heads—what we need to live.

In order to be able to recognize the specific, material, life-sustaining value of things and services instead of purely their cash value, we need a new term: “Subsistence production”—or production of life—which includes all work that is expended in the creation, re-creation, and maintenance of immediate life and which has no other purpose. Subsistence production therefore stands in contrast to commodity and surplus value production. For subsistence production the aim is “life,” for commodity production it is “money,” which “produces” ever more money, or the accumulation of capital. For this mode of production life is, so to speak, only a coincidental side-effect (Mies & Bennholdt-Thomsen, 1999; see also Bennholdt-Thomsen, 2011).

The principles of a policy of subsistence:

1. Subsistence politics is a politics of everyday life, taken from the “bottom” of active, responsible individuals and not from “above,” from a higher authority.

2. Subsistence politics is a politics of necessity, of immanence rather than transcendence.

3. The policy for subsistence is based on the concrete, material substance, corporeal, sensuous, and opposes the abstraction of money and the anonymity of the goods.

4. Subsistence orientation is a policy for the restoration of community.

The subsistence perspective reminds us that climate change and the social disintegration we relentlessly encounter today are the consequences of a Western worldview and its growth as the crucial measure of success. Maternal and indigenous ways of thinking show us that there are alternatives and other sources of inspiration. As such, the subsistence politics points the way out of the growth-oriented economy and towards the gift economy and solidarity economy. (Bennholdt-Thomsen, 2015, p. 200)

***Vicki Noble, a spiritual guide, healer, and scholar, is brave enough to stand out against the anti-essentialist feminists (and thus, Mann’s ally). In so doing, she confirms what I felt intuitively but—without a supportive community and under pressure from feminist colleagues in academia—was unable, in fact, frightened, to voice my own thoughts.

Vicki Noble taught me to honor Blood Mysteries—women’s biological cycles, rather than being considered “essentialism” or “biology is destiny” in the Freudian sense—the primal link to alignment with natural law. Indigenous people around the world still honor and relate to these female lunar cycles as part of the legacy they pass on to the next generation. Giving birth is not “reproduction.” We are not reproducing or creating continuity to ourselves but creating something new, different, original, and unique.

This glib label, essentialism, says Vicki Noble (2017), has caught on in our culture in such a way that any assertion about women sharing certain qualities or traits, despite their cultural differences, is met with disdain. With the recent significance of transgender politics and theory, being an essentialist is practically illegitimate. Yet, it is only women who bleed, give birth, and nourish babies from their breasts; this potentiality is shared regardless of whether individual women within a group choose to give birth.

Although the fight-or-flight response to stress was once assumed to be universal in humans, Noble says, more recently scientists have shown it to be a male response stimulated by the production of testosterone. Females under the same stressful circumstances have an entirely different response stimulated by the production of oxytocin (the so-called “bonding hormone”), a response Dr. Shelley Taylor (2002) calls the “Tending Instinct.” Rather than aggression or flight, females collectivize by gathering in the children and collaborating with other females on what to do.

Vicki Noble also tells us that “the central icon of matriarchal agricultural societies was the Goddess—the abundant and generous Mother of All Things—whose centrality begs to be re-established today along with women in leadership as her ministers.” Noble traces the image of the life-giving Goddess from prehistoric cave drawings of vulvas through the Venus figurines and ceramic vessels discussed by Marija Gimbutas (1991). Ancient Asian women leaders functioned as Dakinis and Yoginis and female shamans in Mongolia. Bakers of bread in ancient Greece were connected with rituals around pregnancy, healing, and birthing, while, contrary to patriarchal interpretations, female communal agriculture provided an early model of a peaceful society without private property. Modern witches belong to a long line of powerful women of many cultures who have threatened patriarchy and borne the brunt of its reprisals. Noble further suggests that group leadership of women was a crucial (biological) cause in turning matriarchal societies into peaceful communities, as evidence shows conclusively that when women are unified as a group, the hormone oxytocin is generated en masse (Noble, 2007).

Spirituality and shamanism are central and meaningful in matriarchal and indigenous societies. All my maternal teachers deal with and embrace them; yet, Vicki Noble (1990) has been the one who put these issues at the center of her being, doing, and thinking:

Snake Power, to me, is the reemergence of the shamanic religion of the Goddess that will not die. It is a force that goes underground during times of intense oppression and then bubbles up through the body to make itself felt in the population once more. Female shamanism, as I perceive it from my research and my experience, is an earth-based religious calling that brings with it healing power and spiritual leadership. It is awakening right here, right now, in North America (as well as other places) and it is making itself known through ‘white’ women as well as women of color here and in other countries. Female shamanism arises from the female body of the Earth herself, like an impulse for survival and healing that impels us toward right action. The feelings, behaviors and experiences that come with this shamanic awakening have been cataloged and described by people from everywhere in the world. (p. 55)

She further explains: “I am using shaman as a generic word here, as in the general definition from the American Heritage Dictionary: ‘A member of certain tribal societies who acts as a medium between the visible world and an invisible spirit world and who practices magic or sorcery for the purposes of healing, divination, and control over natural events’” (Noble, 2003, p. 9). Noble also demonstrates in her book that these female functions of priestess or shaman were original to and fundamentally alike in different locations around the globe and that their shared traits can be seen in the artifacts and images left to us from their settlements, cult sites, and burial sites.

Western civilization and the Enlightenment as one of its core perspectives are based on rational and critical methods and do not leave room for the mystical, spiritual, and emotional dimensions (perhaps the emotional gets more space since Freud). Following my maternal teachers, though, I believe that spirituality is important for social change and transformative activism. Spirituality is the way we conceive ourselves, our relations with the sublime, the divine, and our mission as human beings in the globe. It defines the elements we value, how we define “success” and how we perceive change. Thus, for example, a feminist change will not be defined in negative terms on the spiritual dimension (e.g., elimination of violence against women) but in positive terms: how we build a world of peace and tranquility.

Spirituality is an inclusive and integrating power that reflects the interconnectedness of all human and non-human beings. It is important since spiritual linking to Nature, community, and culture is crucial for the wellbeing of each individual and society at large. The loss of the spiritual means losing Mother Nature and estrangement from the Other—which led to the current Pandemonium.

Basically, says Claudia von Werlhof (2007a), spirituality is a notion that is always related to wild nature, and that does not see nature as exclusively material, but also as mind and soul—we could also say: as alive. Spirituality is embedded in the vitality of nature. This is my notion of spirituality, hence “earth spirituality.” To view it not as dead matter but rather as expressing the affection that is inherent in life it should be understood as interconnectedness of all being—the intrinsic links between everything there is. Everything is tied together; everything is connected with each other. We are not in the world as human beings alone. Separation is fictitious. The notion of interconnectedness of all being guides us back to the unity that truly exists underneath all. The notion of interconnectedness, in which love and knowledge belong together. Interconnectedness means that we are connected and feel mutually bound in solidarity in a decisively caring environment to which we belong. Furthermore, the concept requires a call for action, namely, to take a stand in the defense of all being and its interconnectedness, and I mean on all levels. Only through this will we be able to feel and take on responsibility.

Spirituality is also connected to the mother and the gift:

If we had the prototype of the mother for the category ‘human’ instead of the father or anyway the adult male, we would have a different kind of religion, which like the mother would be more open to the ‘other’—in terms of other people, other species, and other manifestations of Gaia or Mother Earth.

The modern scientific Gaia hypothesis, that the Earth is alive though in a somewhat different way than we are (and of course we are part of Her) also lets us look at Earth spirituality as maternal, gift giving spirituality. I think the ecological niches fit together in a pattern of giving and receiving. (Vaughan, personal communication, February 11, 2018)

***Doctor and lawyer Angela Dolmetch, an inspirational and innovative Colombian feminist and human rights activist and scholar, established in 2003 the ecovillage Nashira, which provides a livable example of a modern matriarchal community constructed, led, and managed by women. In Nashira, under the leadership of Dolmetch, a group of women—heads of their families from poor, disadvantaged sectors—creates its own housing solutions, cooperative production centers, and workplaces within the framework of sustainability and self-sufficiency. For initiating and building this community, Angela Dolmetch received the Colombian National Award (Dolmetch, 2015).

Unsurprisingly, the Kurdish women are also now founding Jinwar (Women’s space)—where women will gather, live, and work together, based on the vision of a free and communal life. It is a pioneering project that is deeply attached to the three basic principles of the democratic confederalist paradigm: democracy, ecology, and women’s liberation.31

These seven innovative thinkers and activists—together with the many members of our global networks that space is too short to present—are my great teachers, in the most profound meaning of the word. They taught me ethics and beauty, to hope and to imagine, to envision an alternative world, and to live my vision. They have been and still are an important source of new learning and inspiration for me, transforming my ways of knowing and activism. They enabled me to re-connect to women’s legacy that has been silenced and ignored for centuries, to engage with Rematriation. They lead me into the symbolic order of the mother. They even re-connect me—a secular Jew who strongly rejects many Jewish ideas and religious politics—to some Jewish thought (indeed carefully and critically). With their guidance and support, I discovered ways of thinking and living that had been unknown to me. They, in particular, open the door for me to imagine a different kind of human behavior and another social order that are consistent with my values.

23 The presentations of the wisdom of these teachers are based on my readings of their many books and publications.

24 See her books and articles at Gift-Economy.Com which also presents articles on the gift economy published by numerous writers and scholars.

25 I am grateful to Vaughan for her comments on this paragraph.

26 See her numerous books, articles, and presentations: https://www.hagia.de/en/international-academy-hagia/

27 http://www.ganienkeh.net/thelaw.html.

28 Binary—a pair of related terms or concepts that are opposite in meaning.

29 The Torah of Israel does not oppose evolution, on the contrary, it refines it, gives it direction—it shows and emphasizes that the development was and still is made in a specific direction http://www.daat.ac.il/daat/tanach/maamarim/torat-2.htm. Prominent scientist and Jewish scholar Prof. Yeshayahu Leibowitz (like other prominent Jewish scholars) thinks so too. He further accords priority to the oral Jewish tradition over the written Bible. See https://he.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D7%99%D7%97%D7%A1_%D7%94%D7%99%D7%94%D7%93%D7%95%D7%AA_%D7%9C%D7%AA%D7%95%D7%A8%D7%AA_%D7%94%D7%90%D7%91%D7%95%D7%9C%D7%95%D7%A6%D7%99%D7%94#%D7%99%D7%A9%D7%A2%D7%99%D7%94%D7%95_%D7%9C%D7%99%D7%91%D7%95%D7%91%D7%99%D7%A5. Thus, too, can Mann’s story of creation be understood.

30 And as such, it is also connected to the Jewish legacy (Pedaya, 2018) https://www.haaretz.co.il/literature/study/.premium-1.6479462 [Hebrew].

31 https://internationalistcommune.com/jinwar/ and https://www.facebook.com/jinwarwomensvillage/.

קוראים כותבים

There are no reviews yet.